In

our northern Minnesota beds, Cyp. guttatum does very well in a very

sandy substrate with an over-layer of composted bark or leaves or some

other light humus.

In

our northern Minnesota beds, Cyp. guttatum does very well in a very

sandy substrate with an over-layer of composted bark or leaves or some

other light humus.

Cyp.

guttatum is one of our most beautiful slipper species. In suitable

climate and soil conditions, the creeping rhizomes of the plant spread

almost as a ground cover. The bad news is that this Alaskan plant

does poorly or fails altogether in climates with hot summers and/or mild

winters. We recommend this species only for the northern tier of

the lower 48 U.S. states, northern Vermont, or at high elevation in mountainous

regions.

Cyp.

guttatum is one of our most beautiful slipper species. In suitable

climate and soil conditions, the creeping rhizomes of the plant spread

almost as a ground cover. The bad news is that this Alaskan plant

does poorly or fails altogether in climates with hot summers and/or mild

winters. We recommend this species only for the northern tier of

the lower 48 U.S. states, northern Vermont, or at high elevation in mountainous

regions.

In

our northern Minnesota beds, Cyp. guttatum does very well in a very

sandy substrate with an over-layer of composted bark or leaves or some

other light humus.

In

our northern Minnesota beds, Cyp. guttatum does very well in a very

sandy substrate with an over-layer of composted bark or leaves or some

other light humus.

Cyp.

guttatum is one of the most colorful Cyp species. Under good

conditions it reaches a height of over 20 cm (8 inches).

Cyp.

guttatum is one of the most colorful Cyp species. Under good

conditions it reaches a height of over 20 cm (8 inches).

Cyp.

kentuckiense has the largest flowers in the whole genus. This

species is one of the most adaptable to varied climates. Although

its natural range is from the state of Kentucky south to Louisiana, it

manages to survive winters here in northern Minnesota and even grow from

year to year, although it makes faster progress in climates with a longer

growing season.

Cyp.

kentuckiense has the largest flowers in the whole genus. This

species is one of the most adaptable to varied climates. Although

its natural range is from the state of Kentucky south to Louisiana, it

manages to survive winters here in northern Minnesota and even grow from

year to year, although it makes faster progress in climates with a longer

growing season.

These

are two Cyp. kentuckiense seedlings flowering for the first time.

Note the unusually exquisite coloration of the plant on the left.

These

are two Cyp. kentuckiense seedlings flowering for the first time.

Note the unusually exquisite coloration of the plant on the left.

Here

is a close-up view of the left-hand plant in the previous photo.

In the future, this plant should be great breeding stock.

Here

is a close-up view of the left-hand plant in the previous photo.

In the future, this plant should be great breeding stock.

Here

is a bed of Cyp. parviflorum var. pubescens. The whole

bed contains seedlings beginning their third year out of the flask.

Some of the plants shown here also bloomed last year. We wish we

could say that this is typical of third year seedlings, but overall, only

about 10% of the seedlings in this bed bloomed, and they were all located

at one end of the bed. All the seedlings in the bed were planted

in the same medium, so it is a mystery why the plants at one end of the

bed have grown faster than the others.

Here

is a bed of Cyp. parviflorum var. pubescens. The whole

bed contains seedlings beginning their third year out of the flask.

Some of the plants shown here also bloomed last year. We wish we

could say that this is typical of third year seedlings, but overall, only

about 10% of the seedlings in this bed bloomed, and they were all located

at one end of the bed. All the seedlings in the bed were planted

in the same medium, so it is a mystery why the plants at one end of the

bed have grown faster than the others.

This

photo shows the same Cyp. parviflorum var. pubescens bed

as in the previous photo but one year later, i.e., the seedlings are beginning

their fourth year out of the flask.

This

photo shows the same Cyp. parviflorum var. pubescens bed

as in the previous photo but one year later, i.e., the seedlings are beginning

their fourth year out of the flask.

Growing

Cyp.

reginae in northern Minnesota is not difficult. Here we have

a bed with seedlings of varying ages. The largest plant on the left

is 12 years old, while there are young plants at the right that have not

yet bloomed.

Growing

Cyp.

reginae in northern Minnesota is not difficult. Here we have

a bed with seedlings of varying ages. The largest plant on the left

is 12 years old, while there are young plants at the right that have not

yet bloomed.

The

Cyp.

reginae garden plant shown here was photographed at 10 years out of

the flask. When the photo was taken, the plant had 26 flowers.

It has even more now although growth is slowing down. Such large

clumps can be divided to yield many more plants.

The

Cyp.

reginae garden plant shown here was photographed at 10 years out of

the flask. When the photo was taken, the plant had 26 flowers.

It has even more now although growth is slowing down. Such large

clumps can be divided to yield many more plants.

The

color of Cyp. reginae flowers varies considerably. Plants

growing in full sun frequently have pale flowers, whereas plants in shady

locations often have deep pink on the lip.

The

color of Cyp. reginae flowers varies considerably. Plants

growing in full sun frequently have pale flowers, whereas plants in shady

locations often have deep pink on the lip.

Cyp.

reginae forma albolabium is a very rare plant. We now

have several such flowering seedlings, some with multiple flowers.

Cyp.

reginae forma albolabium is a very rare plant. We now

have several such flowering seedlings, some with multiple flowers.

This

is a close-up of the albolabium seedling in the previous photo.

This

is a close-up of the albolabium seedling in the previous photo.

Cyp.

reginae forma albolabium in the foreground contrasts with normally

colored Cyp. reginae behind.

Cyp.

reginae forma albolabium in the foreground contrasts with normally

colored Cyp. reginae behind.

The Planting Mix

The most important consideration in planting Cypripedium seedlings is to provide a well-aerated environment for the roots. The planting mix should have an abundance of air spaces, and these spaces should never be allowed to fill completely with water. In nature, the requirement for a well-aerated substrate is met in a variety of ways: in light fluffy humus, in soil that is largely sand, in gravel, and in living sphagnum moss where the roots enjoy the large air spaces among the moss fibers. Magnificent Cyp. pubescens plants have even been found growing in squirrel middens consisting of old pine cone fragments. In planting Cyp seedlings, think fluffy.

Provision of such a well-aerated medium in cultivation can be tricky. Simply putting soil, even rich woods soil, in a pot results in a highly compact medium that suffocates Cyp roots. The solution is to dilute the soil greatly with perlite or some other highly porous material. We have found that perlite is the cheapest and most widely available such material. A planting mix of two or three parts perlite to one part of light humus, hardwood forest duff, or leaf mold works very well for potting most North American Cypripedium species. Be very sure not to use clay or a clay-rich soil in the mix.

Some commercial soil-less potting mixes work well for

potting Cyp seedlings. For a couple years we were using Scott's  Metro-Mix

366-P very successfully for potting without adding any additional perlite.

This is a light, fluffy mix consisting of 30-40% coconut coir pith, 20-30%

horticultural vermiculite, 20-30% composted pine bark, and 10-20% perlite.

This product does not contain peat moss which tends to hold too much water

and to become soggy. Metro-Mix 366-P has become increasingly difficult

to find and may no longer be manufactured. Metro-Mix 560, another

product based largely on coir and composted pine bark, may be a suitable

substitute for 366-P, but 560 does contain a little peat and so should

probably be mixed with additional perlite.

Metro-Mix

366-P very successfully for potting without adding any additional perlite.

This is a light, fluffy mix consisting of 30-40% coconut coir pith, 20-30%

horticultural vermiculite, 20-30% composted pine bark, and 10-20% perlite.

This product does not contain peat moss which tends to hold too much water

and to become soggy. Metro-Mix 366-P has become increasingly difficult

to find and may no longer be manufactured. Metro-Mix 560, another

product based largely on coir and composted pine bark, may be a suitable

substitute for 366-P, but 560 does contain a little peat and so should

probably be mixed with additional perlite.

As Metro-Mix 366-P or 560 is not always easy to find, however, a good alternative is to prepare the mix yourself from readily available constituents. We are currently using a mix that is three or four parts perlite to one part coir. Coir is available from many larger horticultural suppliers and online vendors. The material is usually shipped as compact blocks or bricks. The user simply adds the block to a tub of water to prepare the material for use. Some care must be used to obtain coir that has not been washed with sea water before export from the source, as the sea water leaves a residue of salt that his harmful to orchids. If the original source of the coir is inland, away from an ocean, the product is probably sufficiently salt-free. If in doubt, give the coir several rinses in fresh water to remove any salt residue that may be present. Coir has excellent cation exchange capacity, much higher than perlite, and thus can provide a source of nutrients to the orchids. The coir itself, however, does not contain these nutrients; they must be added by occasional application of fertilizer. The coir simply retains the nutrients from the fertilizer solution and makes them available to the plants.

Another product that is very promising is TurfaceŽ MVP. This material is a ceramic made by firing clay granules. TurfaceŽ is quite similar to the European product Seramis, which Cyp growers there have been using satisfactorily for years. Like coir, TurfaceŽ adds cation exchange capacity to the mix. We have been using TurfaceŽ satisfactorily by mixing it with perlite at a rate of one part TurfaceŽ to two, three, or four parts perlite. By itself TurfaceŽ seems to hold somewhat too much water and tends to make the mix too wet unless added to another ingredient like perlite or sand. As with coir, TurfaceŽ itself is not a source of nutrients; they must be added by a light application of fertilizer. TurfaceŽ can be difficult to find. It is used as a top dressing for athletic fields to soak up excess moisture. If you can't find the product at a horticulture supply dealer, try a business that landscapes baseball fields.

For outdoor beds, sand should be used to produce porosity,

not perlite. In outdoor beds, perlite, because of its low density,

gradually floats up to the surface so that the material below becomes too

compact. In outdoor beds, the planting mix should consist of two,

to as much as four, parts sand per one part humus or TurfaceŽ.

Planting in Pots or Flats

When planting in pots, each seedling should be placed in a pot eight inches or more in diameter if the seedling is expected to reach blooming size in the pot. In general, Cypripedium roots tend to spread more laterally than downward, so a shorter pot such as an azalea pot will conserve planting mix. As described above, the mix should be prepared by diluting organic matter such as humus or coir with perlite. The object is to make a light, fluffy mix, so be sure to use sufficient perlite to keep the mix from compacting.

For planting a large number of seedlings, putting the plantlets in deep flats conserves space. In flats, the plants can share root space with one another, so that they can be placed much closer together than they would be in individual pots.

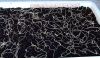

To illustrate planting in flats, the photo at right shows

Cyp. parviflorum var. pubescens seedlings distributed in

a flat before  being

buried. A layer of planting mix is first laid down in the deep flat.

Then the seedlings are place on this layer with their roots more or less

horizontal and their shoots vertical. While the roots appear

crowded, the emergent leaves will not be, at least not the first year,

and the plantlets will make excellent growth in such a flat. Plants

can usually be left with this spacing in a flat for two growing seasons.

Note the ruler for scale.

being

buried. A layer of planting mix is first laid down in the deep flat.

Then the seedlings are place on this layer with their roots more or less

horizontal and their shoots vertical. While the roots appear

crowded, the emergent leaves will not be, at least not the first year,

and the plantlets will make excellent growth in such a flat. Plants

can usually be left with this spacing in a flat for two growing seasons.

Note the ruler for scale.

More

mix is then added by hand until the roots are entirely covered and the

tips of the shoot buds barely protrude above the surface of the mix as

shown in the figure at the left The ruler gives the scale.

More

mix is then added by hand until the roots are entirely covered and the

tips of the shoot buds barely protrude above the surface of the mix as

shown in the figure at the left The ruler gives the scale.

The

photo at left shows the seedlings in the flat a couple months after planting.

The

photo at left shows the seedlings in the flat a couple months after planting.

The picture at the right shows a smaller flat containing

Cyp.

pubescens seedlings in their third year in the flat. The flat

in this photo is smaller than the one shown in the previous three photos,

and some of the seedlings are now five to six inches high.

The plants should probably have been transplanted before

this third growing season as they are liable not to grow much in such crowded

conditions. The ferns in the "understory" do not help growth of the

orchids and should have been removed as weeds.

Vernalization

Cyps are temperate plants and require a dormant period

spent at nearly freezing temperature to reset their metabolism to produce

leaves in the spring. People in climates with cool, humid summers

but warm winters often have the frustrating experience of growing the plants

successfully through one summer only to have them fail to reappear the

next spring because winter temperatures were not low enough to vernalize

the plants. Cyps can be grown in climates with warm winters but only

if the plants are given artificial refrigeration during the winter.

Fertilization

Horticultural literature commonly states that lady's-slippers

should not be fertilized. Cyps, however, like most plants, need nutrients.

The complication is that Cyps cannot tolerate high concentrations of some

nutrients such as nitrogen. The proper treatment of Cyp seedlings

is to water them occasionally with a very dilute, no more than one fourth

the recommended strength, solution of fertilizer. We are currently

using Dyna-GroŽ 7-9-5 at a rate of 1/4 teaspoon (1.2 mL) per 2 gallons

(7.6 L) of water and applying this solution for every other watering of

the plants.

Hazards

Because of their small size, Cyp seedlings are very fragile. They are no more fragile than other small seedlings such as trilliums or columbines, but all such little plants are very vulnerable. The seedlings must be protected from all kinds of hazards, some obvious, and others unsuspected. Predators such as insects and slugs can consume the plants as quickly as they can grow above ground. Non-predators including chipmunks, squirrels, mice, birds, cats, and dogs often destroy Cyp seedlings simply by digging in freshly planted beds. In the wild, hail storms sometimes strip Cyp plants of their leaves, and such hail can quickly kill tiny seedlings. Heavy rains often wash soil away from the roots of Cyp seedlings, and exposed roots quickly dry out killing the plantlet. Because of their small size, even correctly planted seedlings have roots very near the surface, and these shallow root systems are vulnerable to desiccation.

The solution to all these problems is diligence. Seedlings should be inspected daily. Many predators can be fended off by encircling seedlings with hardware cloth or inverting a plastic berry box over them. Watering seedlings during dry periods is essential. If you are sufficiently sedulous and succeed in growing your plants to maturity, then you will have to worry about predation by deer!

References

The monograph by Cribb listed below is a very important work on Cypripedium taxonomy and is indispensable for any serious collector of Cyps. We list the book here because it also contains an excellent chapter by Holger Perner on cultivating Cyps. This chapter contains a wealth of information about growing most Cyp species and is especially valuable for the culture of Asian Cyps, material that is not widely available elsewhere.

The paperback by Bill Mathis is particularly useful for growing North American native orchids, including Cyps, and very well illustrated. If you don't grow native orchids now, you'll probably want to after seeing this book!

Cribb, Phillip. 1997. The Genus Cypripedium. Timber Press.

Mathis, William. 2005. The Gardener's Guide to Growing

Hardy Perennial Orchids. The Wild Orchid Company.